Aurora chasers could be in for a treat this month. As the September equinox approaches, two key phenomena—the Russell–McPherron effect and the equinoctial effect—are expected to boost auroral activity in the coming weeks.

What is the aurora?Why the Equinox Sparks Auroras

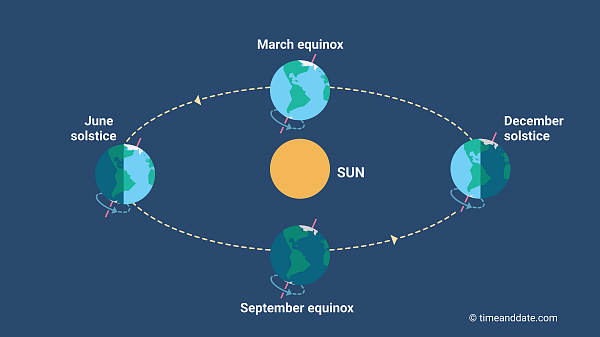

At the equinoxes, Earth’s axis is tilted neither toward nor away from the Sun. This geometry shapes how Earth’s magnetic field interacts with the solar wind: Earth’s magnetic field points north, and when the solar wind’s magnetic field points southward—opposite to Earth’s—the two fields can connect, a process called magnetic reconnection.

This process lets energy and charged particles from the Sun stream into Earth’s magnetosphere, powering auroras.

Think of it like two magnets: if their poles are opposite, they snap together; if they’re the same, they push apart. Around the equinoxes, Earth’s tilt positions its magnetic field so that we more often experience the solar wind’s magnetic field pointing southward, opposite Earth’s, allowing the two fields to connect.

Even when the solar wind’s magnetic field isn’t southward, auroras can still occur, though they tend to be stronger and more frequent when the field points south, opposite to Earth’s.

Because this alignment happens more often around the equinoxes, auroras in both hemispheres become brighter and more frequent—this phenomenon is known as the Russell–McPherron effect.

The Equinoctial Effect

Scientists point out that another factor—called the equinoctial effect—also boosts auroras.

Around the equinoxes, when Earth’s tilt is effectively zero relative to the Sun, our planet’s magnetic poles fall nearly at right angles to the solar wind. This orientation makes Earth’s magnetosphere—our planet’s invisible shield—more open to interactions with the solar wind, allowing energy and charged particles to enter.

Our in-house astrophysicist, Dr. Renate Mauland-Hus, explains how this essentially makes our magnetosphere a bigger target for incoming solar wind.

The equinoctial and Russell–McPherron effects are neat interplays between geometry and magnetic fields. When they coincide at the equinox, the night sky can put on some of the most memorable auroral shows of the year.

Dr. Renate Mauland-Hus, timeanddate.com

Some scientists also point to a third, weaker component called the axial effect. It relates to Earth’s position relative to the Sun’s equator, which may also play a small role in boosting auroral activity around the equinoxes.

Solar Maximum: An Extra Boost

This year, the timing is especially favorable. The Sun seems to be just past the peak of its solar maximum phase—the period in the 11-year solar cycle, when solar storms and Earth’s geomagnetic activity are stronger and more frequent.

These storms can produce both coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and faster, denser solar wind, supercharging the northern and southern lights.

The combination of solar maximum and the September equinox gives skywatchers one of the best chances to see auroras in over a decade.

When and Where to See

For aurora hunters, this combination of factors means the weeks around the September 22 equinox are prime time for auroral viewing. Geomagnetic storms are still required to create visible displays further from the polar regions, but the odds are tipped in favor of more frequent and brighter aurora displays around this time of year.

The Northern Lights

In the Northern Hemisphere, the next several weeks could bring ideal viewing conditions for high-latitude regions such as Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia, and the northern parts of the UK.

Strong solar storms can cause the northern lights to light up skies much further from the usual auroral zones, sometimes as far south as the northern US or central Europe.

The Southern Lights

In the Southern Hemisphere, the aurora australis can be visible from Tasmania, New Zealand, southern parts of South America, and occasionally even South Australia during strong geomagnetic storms.

Fewer people live under the southern auroral oval—the area around the poles that usually gets the aurora—but those who do may enjoy darker skies and less light pollution, making the equinox boost especially rewarding.

Don’t Miss It

Around the equinox, when Earth’s tilt is effectively zero relative to the Sun, the alignment of Earth’s magnetic field and the Sun’s extended magnetic field can make auroras brighter and more frequent across the globe.

Combined with the heightened activity around solar maximum, this means that whether you live under the auroral oval or farther afield, this could be one of the best times in years to witness nature’s incredible light show.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are auroras more active at the equinoxes?

Auroras are more active around the equinoxes because Earth’s tilt and magnetic field align with the solar wind in a way that makes for easier and more frequent interaction between the two, fueling auroras.

Two key factors drive this: the Russell–McPherron effect, where magnetic reconnection is more likely, and the equinoctial effect, where Earth’s tilt makes the magnetosphere more open to the solar wind. Together, these effects boost auroral activity, making the northern and southern lights brighter and more frequent around the equinoxes.

Why is September 2025 a great month to see the Northern Lights?

In September, at the equinox, Earth’s tilt is neither toward nor away from the Sun, maximizing the likelihood of magnetic reconnection with solar wind. Combined with the solar maximum, this creates ideal conditions for vivid auroras, making it one of the best times in years to see the Northern Lights.

How does solar maximum affect auroras?

During the solar maximum, the height of the Sun’s 11-year cycle, the Sun’s activity peaks, producing stronger solar storms, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and faster solar winds. These intensify Earth’s geomagnetic activity, resulting in more spectacular and widespread auroras.

How long will the aurora season last around the equinox?

Auroras are usually most frequent in the weeks around the equinoxes—late March and September. In 2025, the weeks surrounding the September equinox are expected to provide some of the brightest and most frequent auroras in over a decade.

Are auroras visible everywhere?

Auroras are most visible in high-latitude regions near the magnetic poles, but strong geomagnetic storms—especially around equinoxes and solar maximum—can make them visible farther from the poles, increasing the chance of sightings further from the auroral oval.